How to make a budget that doesn't feel useless

Budgets are useless if they're not tailored to you. This article guides you through starting a budget with categories that reflect your unique goals and circumstances.

The internet is littered with articles claiming that "budgets are useless" and you may have the same impression after playing with the idea of starting a budget.

I agree that an impersonal budget, the kind where you jam your expenses into a generic list of pre-prescribed categories and then count receipts every month, is more trouble than it's worth.

This article is about something else entirely: how to create a personalized budget that provides the structure to think through your most important spending trade-offs...and then gets out of the way.

For example, imagine that one of your best friends invites you to a once-in-a-lifetime holiday trip they've planned. As you listen to all the exciting activities they have in store, you start to feel a pang of doubt. This trip will be very, very expensive.

How do you decide whether to go? You won't find the answer in a traditional budget.

This post details the process of setting up a strategic budget. It's Part 2 of a 4 part series on budgeting.

The Budget Series

- Part 1: Why tech workers should have personal budgets

- Part 2: How to start your strategic budget (this post)

- Part 3: Running budget experiments

- Part 4: Refining your priorities (Coming soon)

Follow me on Twitter or sign up for the email newsletter to be notified when part 4 becomes available.

How to start your strategic budget

This post will explain how to start your budget in the easiest way I know how.1

While I've designed these recommendations with tech workers in mind, feel free to modify and extend them to suit you better. Since budgeting is personal, tweaking the process wherever it seems unhelpful to you personally will make it more likely you'll stick to your strategic budget over the long haul.

Now let's get to it!

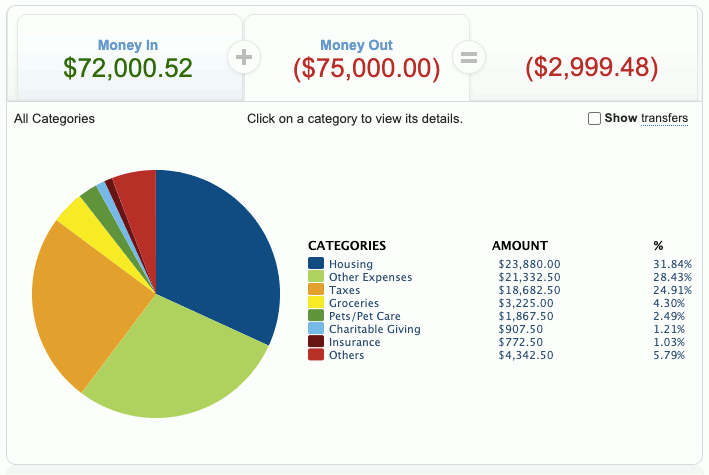

Step 1: Sketch your current money flow

The first step to set up your budget is to create a rough sketch of where your money is currently going. One easy way to do this is to look back at your last 1-3 months of income and expenses and break them down into categories.

Ideally, you can pull most of the spending category totals from your past credit card and bank statements.

Or, in the worst case, if you use a lot of cash, you'll need to go through an entire month's transactions manually by reading last month's receipts or by keeping track of the following month's transactions.

Don't use any budgeting app for now. The mechanics of setting them up will get in your way as you capture your money flow and start thinking about what you want from your money.

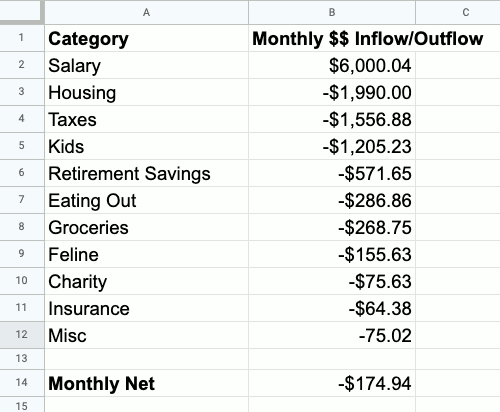

Instead, create a simple spreadsheet with two columns: Category and Monthly $$ Inflow/Outflow.

Avoid judging yourself or pontificating about expenses as you jot your spending down. The purpose of this step is to survey the money you have coming in and where it's going out. Complete comprehensiveness is a non-goal, and there's no reason to track every expense down to the dollar or survey an entire year's expenses. Your budget is a tool to clarify your thinking, not a database.

That said, misleading yourself about your spending in any significant way will only lead you down the wrong path later when you're trying to make decisions based on this information. So if you're missing more than 5% of your total expenses, it's worth tracking them down. If you are avoiding thinking about a category of expenses out of some kind of guilt trip, don't let yourself get away with that either!

Step 2: Humanize your budget categories

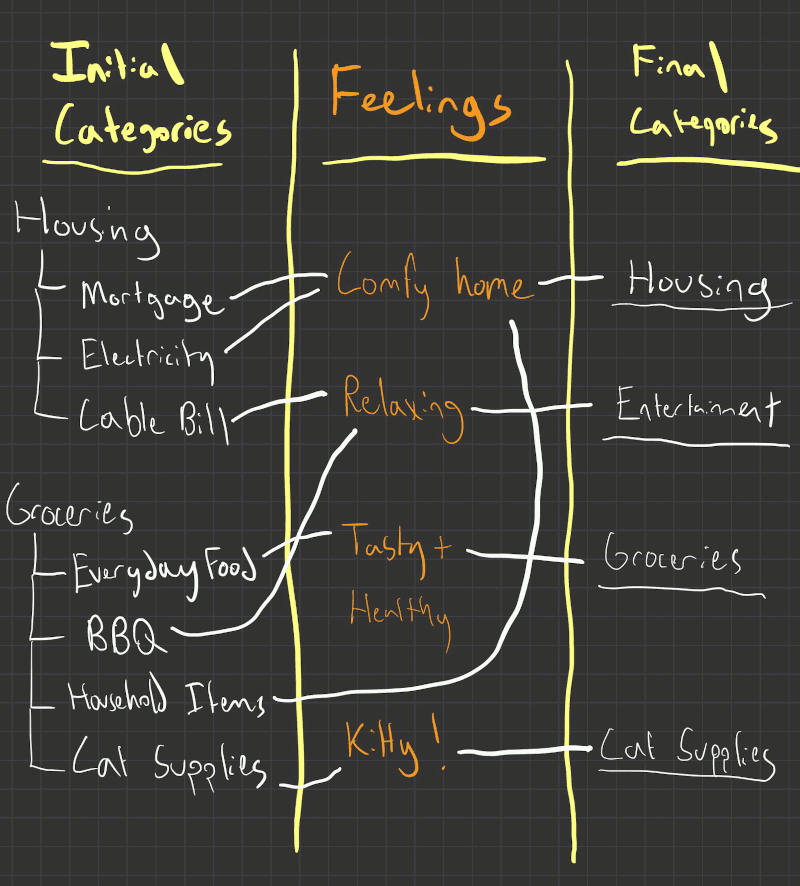

Once you've done the initial documentation of your expenses, the next step is to take the categories and "refactor" them (extending, splitting, merging) so that they capture your personal life outlook.

Categorization is what transforms a budget from a banal accounting document to a tool for reflecting on your unique life choices and circumstances.

Forget whatever categories you think should go in a traditional budget. If they don't capture the nuances of what you love, hate, what you're obliged to do, or are trying to accomplish, they won't help you make the money decisions that will improve your life.

But how do you come up with a list of personal categories?

"Feeling" categories

The best way to develop your budget categories is to look at the expenses you saw in the first step and consider how you would feel without them. In what way would you feel unfulfilled?

That feeling is a budget category.

You should pick budget categories that each feel emotionally different to you when you spend on them. A good budget category represents a distinct pleasure, objective, or responsibility you're trying to satisfy.

Even budget categories that seem emotionless stem from some deeper desire. Your electricity and gas bill keep your home comfortable to live in, and your mobile phone bill is what keeps you feeling connected to your friends and family. You might most easily summarize these feelings as the Home and Communication categories. But the expenses that fall into those categories should generate similar feelings and have the same meaning to you.

Types of budget categories

Although budgets should be deeply personal, most use similar groups of categories ("super-categories"). It's your call whether to include any or all of these super-categories, but thinking through each of them will help you organize your budget.

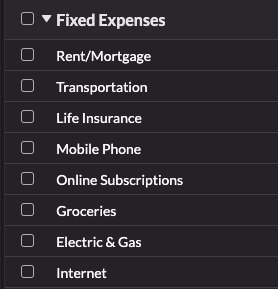

Fixed obligations

These are the easiest to get out of the way first because they immediately come to the top of mind when you think of budgets. Housing, tuition, daycare, insurance, commuting costs, utilities, and groceries are all examples of expenses that stay roughly constant and that you're more or less obligated to pay.

If your fixed obligations have different purposes, try to split them into separate categories.

For example, if you take the train to work, but you also have a car for doing chores, don't lump them both into a Transportation category. Instead, create Commute and Car categories. Similarly, if you rent a server for your programming side-projects, don't lump it into Utilities; create a Side Projects category.

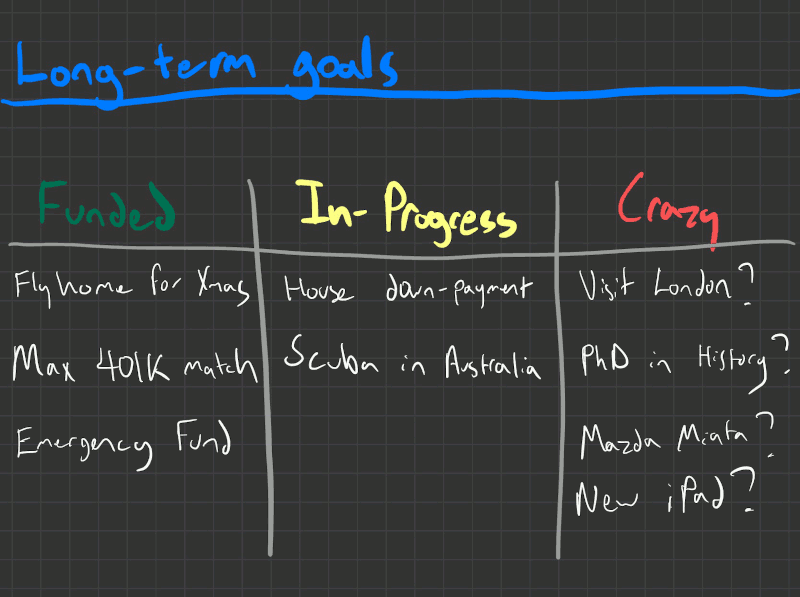

Long-term goals

Each of your long-term goals should have a category. These categories represent expenses that you're not going to pay for any time soon, but that will need some financial cushion if you're going to be able to do them.

Examples of long-term goals vary enormously. They range from life aspirations (early retirement, starting your own business or non-profit) to financial milestones (getting out of debt, buying a home) to organizing special occasions (a trip to the Appalachian trail, saving for a wedding).

These categories could end up being enormously beneficial. First and most obviously, because you won't accomplish high-cost goals unless you plan for and save for them.

But more subtly, it's often not clear which of your aspirations are realistic until you stop swirling them around in your mind and put them on paper. Just "playing through" your dreams by moving money around on your budget can allow you to calibrate how crazy or achievable your musings are.

I always thought it would be interesting to live for several months in a foreign country. I had never considered this a long-term goal because it was just something that passed through my mind when traveling. If I was traveling with a friend, I might remark, "Hm, wouldn't it be cool to see what it's like to live here?"

It seemed like a frivolous daydream. I would never really leave my job and put my future at risk just to fulfill a playful desire to buzz around for a few months in some random country.

But a few things came together that turned my daydream into a reality.

First, a realization of what's possible: I noticed one or two people at my work take extended unpaid leaves. I thought such leaves were only for extraordinary cases, but after talking to them, they seemed routine. Some were even for vacations. I looked into my company's policies, and taking time off didn't seem as risky or challenging anymore.

Second, I acquired motivation: I had met a girl the previous year on vacation in Italy, and we have had a relationship ever since. We were constantly chatting online, teaching each other about our languages and culture, and even arranged a few long weekends in both the US and Italy to spend more time together in person. On those weekends, we talked about the possibility of living together for a while in Italy. But the idea still seemed surreal, like something out of a movie.

Lastly, the budget: I had started budgeting about a year earlier and already had long-term goals that did not include living abroad (annual vacations and retirement savings). It was during one of my budgeting sessions when it clicked:

I had a long-term goal that I hadn't thought through: testing my long-distance relationship by living several months in Italy.

Once I added Live in Italy to my budget and started shifting money from other goals, it was clear that I had a new high priority in my budget. It also became clear that it wasn't at all reckless to delay my financial goals by a few months.

My sabbatical in Italy was incredible, and two years later, my girlfriend and I are still together. I won't attribute it all to budgeting, but the help it gave me will always keep budgeting as part of my routine and in my heart.

For this reason, when developing your more aspirational budget categories, it's an excellent strategy to be uninhibited and exploratory. Throw in categories for new goals whenever you think of them, even if you don't have the budget to allocate to them yet. This works because long-term categories are the most flexible part of the budget.

Although you might be saving for that round-the-world trip now, it's only going to be paid for some time far in the future. You'll be no worse off if your priorities change later and you decide to put the money towards a down-payment on your dream house instead of taking the trip. In fact, you'll be better off because the money will be available for your new goals.

If this still makes you more uncomfortable, you can benefit from long-term planning even without saving. Just create a separate super-category for Crazy Ideas that won't get any budget until you "graduate" them.

Irregular obligations: the known unknowns

Basing your budget solely on the past few months can be inaccurate if you have irregular expenses. And virtually everyone does. These are expenses that come at varying times and in unpredictable amounts like medical or veterinary bills, home and car repair, holiday gifts for family, or (blech) taxes.

Although they're not entirely predictable like a monthly rent bill, they are nonetheless inevitable expenses that need to be in your budget to make an accurate plan. Creating categories for irregular obligations will allow you to continue to focus on your priorities when these expenses crop up and others are scrambling to recover from their "surprise" bills.

How to come up with these categories? After checking off the big categories mentioned above, check your annual credit, debit, and bank year-end reports for large and one-off expense categories.

Planning for everyday fun

Designing a budget for an automaton that slavishly works towards high-minded ideals and responsibilities is bound to fail. You're human, and sooner than later, you'll want to enjoy yourself. And here's the trick: your budget should not only allow you to have fun, but it should also encourage you to do so!

Your budget should force you to Plan for everyday fun. How do you do that?

Create categories for fun activities you do regularly, such as hanging out at your local bar or coffee shop. If you are into more spontaneous and non-recurring events like concerts or weekend trips, set your budget up to save some money each month so you'll be ready when your favorite artist comes to town

I have a two-pronged "planned fun strategy" that includes categories for both my regular fun activities but also a $100/month no-strings-attached Fun Money category. This $100 budget allows me to treat myself without any guilt. I try to force myself to find something different to spend it on every month, and I cherish many of the moments that I did.

I distinctly recall overpaying $20 for a small portion of squacquerone cheese on a whim from Eataly. It costs something like $5 in Italy, but when I saw it, I started craving it immediately and remembered I had the Fun Money category just for moments like this one. Becaue "you only live once?"

The point of this category is to help you find the right trade-offs to maximize your fun without being financially reckless. This means your budget should call for frivolity, not renounce it!

Don't be overly strict about policing your fun category, or you'll end up resenting your budget and disregarding it entirely. I occasionally go over-budget my fun budget, and I never sweat it. I use it as a reminder that I'm prioritizing my happiness while also catching myself before I go completely out of line.

So go treat yourself to some squacquerone (or whatever it is that gives you joy)!

Emergency and investment funds

If you don't already have them covered, consider adding categories for an Emergency Fund and Investment Fund. I'll touch on them only briefly here since future posts will go into more detail.

An emergency fund is a backstop for when life catches you by surprise. It's intended to be used when you incur major shocks like job loss or a huge medical bill. Depending on your circumstances, an emergency fund of 3-12 months worth of expenses is usually prudent. Use an Emergency Fund budget category to build up your fund or replenish it after an emergency.

Depending on how much slack is in your other budget categories, it might not be necessary to have a large emergency fund. For example, suppose your annual vacation category is worth 12 months of mandatory expenses (that sounds extravagant, but I won't judge). In that case, you could probably cancel your vacation in a pinch and use the funds for an emergency.

The investment fund is where you'll stash any money for which you don't have a short-term use. Since investments can compound into a significant source of income, you'll always want to consider the trade-off between allocating your budget towards short-term desires or investments. Later, we'll examine this trade-off in-depth, but I'd recommend you add this category by default and, at a minimum, devote any "leftover" money to the category.

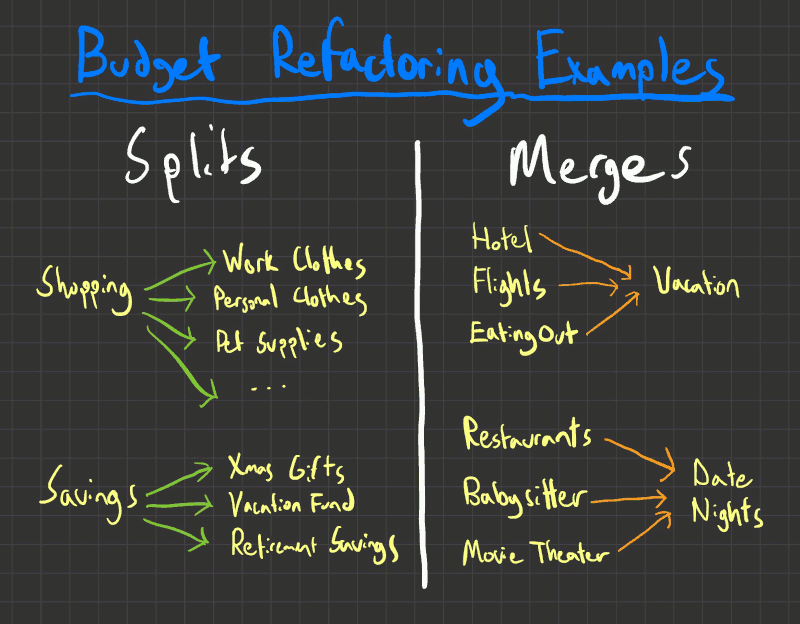

Step 3: Refactor your budget categories

After you've drafted your initial list of categories, you'll need to contemplate whether they're all meaningful and unique and then merge/split the categories that don't meet the criteria. You'll need to repeat this process periodically as your goals and circumstances change.

A couple of examples will help illustrate how to do it.

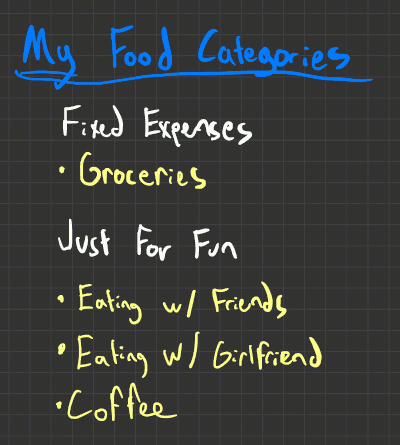

Splitting Example: Food

Food is an expense that we all have, but it's usually a terrible budget category.

There is the food we buy to enjoy at home, the food we buy to scarf down at work, and the food we buy to celebrate with friends and family. Then there's the food we buy because we have no time to cook, the food we buy as part of the new diet, or the food we buy because we had a terrible day.

You get the point -- many different kinds of "Food" have drastically different importance to us based on the context. Only you can decide what categories make sense in your budget.

Budget categories can be as broad or as narrow as necessary to reflect your personal outlook. If food is just fuel to you, maybe there's no need to distinguish between food expenses. If Pasta is one of the reasons you wake up every morning, perhaps it should have a category of its own.

Merging example: A night out

Another pitfall is categorizing related expenses into multiple "traditional" budget categories rather than towards the personal purpose they fulfill for you.

Take the example of having a drink with a close colleague after a long week at work. "Paying for drinks" and paying for a taxi trip home might traditionally be seen as expenses that fall into two budget categories (Entertainment and Transportation). But they’re likely in service of a single desire (Time with friends) and should be part of the same budget category that captures that priority.

After you've sobered up and analyze your budget, you'll be able to distinguish whether you have an "Uber addiction" or are simply prioritizing sharing time with your friends.

Go ahead and do it

If you haven't already, go ahead and start drafting your budget categories!

I've included an example budget below to help you get started, but remember that your budget should reflect your unique personality and not be anchored to anyone else's categories.

The following article in the series will explain how to use the budget categories you've started to plan experiments and generate insights about your spending.

| Fixed Obligations | |

|---|---|

| Personal | |

| Mortgage/Rent | $2,200 |

| Childcare | $1,000 |

| Groceries | $500 |

| Utilities | $200 |

| Insurance | $175 |

| Giving | $50 |

| Work | |

| Commuting | $250 |

| Supplies | $20 |

| Irregular Expenses | |

| Planned Fun | |

| Eating out | $100 |

| Eating in | $100 |

| Entertainment | $200 |

| Fun Money | $50 |

| Surprises | |

| Home Improvement | $100 |

| Clothes | $100 |

| Medical | $200 |

| Online subscriptions | $100 |

| Stuff I forgot to budget | $100 |

| Longterm Savings | |

| Mandatory | |

| Retirement savings | $500 |

| Vacation fund | $150 |

| College savings | $200 |

| Extra taxes | $100 |

| Aspirational | |

| Home down-payment | $200 |

| Open my own business | $10 |

| Buy a boat | $0 |

Key takeaways:

-

The first step to creating your budget is to identify meaningful categories

-

The easiest way to do this is to look at your past 1-3 months expenses and put them into categories that each have a specific purpose or meaning to you personally