Running budget experiments for fun and profit

Crafting a perfect budget in one shot is impossible. This article explains how to optimize your time and money by running budget experiments iteratively.

You are wasting time and money on things that aren't important to you. We all are. It's only human nature.

We have an imperfect understanding of ourselves, a fuzzy memory about what brought us happiness in the past, and are utterly incapable of predicting the future.1 So it would be delusional to think that we can sit down and plan the perfect budget. At least in a linear way.

But with an iterative approach to budgeting, you have a better shot. I've created this method of budget experimentation, incorporating my own experience as a software engineer, and adapting advice from other personal finance experts.2

Much like agile software development, budget experiments provide the chance to iteratively test out ideas about your spending, reflect, and then change tack. Over time, they will stop you from wasting your time and money by aligning your spending with your pleasures and life goals.

This post explains what budget experiments are and how to run them. It's Part 3 of a 4 part series on budgeting.

The Budget Series

- Part 1: Why tech workers should have personal budgets

- Part 2: How to start your strategic budget

- Part 3: Running budget experiments (this post)

- Part 4: Refining your priorities (Coming soon)

Follow me on Twitter or sign up for the email newsletter to be notified when part 4 becomes available.

Running budget experiments

What are they?

After selecting your hyper-personalized budget categories, it is time to introspect.

Examining how much you spend on each category, you'll likely find that your budget doesn't perfectly match your self-image. Ask yourself the following questions:

- Which categories make you feel pride, joy, guilt, or frustration?

- Which categories surprisingly make you feel little or nothing?

- Does your budget reflect who you are as a person?

For some categories, you'll easily recognize a discrepancy and immediately resolve to change them.

Easy Example:

"Damn, I'm the person with the $99/month gym membership I never use. If I can't get myself to go this week, I'll cancel."

But the more illuminating cases are not just about money. Instead, they stem from feelings that you'd be happier if you could change something, even if you can't put your finger on the what or why.

More ambiguous examples:

"I don't like paying $200/month for my horrible commute to work, but I chose where I live and where I work."

"With the money coming in, it'll be five years before I save enough to visit Japan at this rate. I can't wait that long."

Budget experiments help you work through and resolve these more ambiguous financial issues.

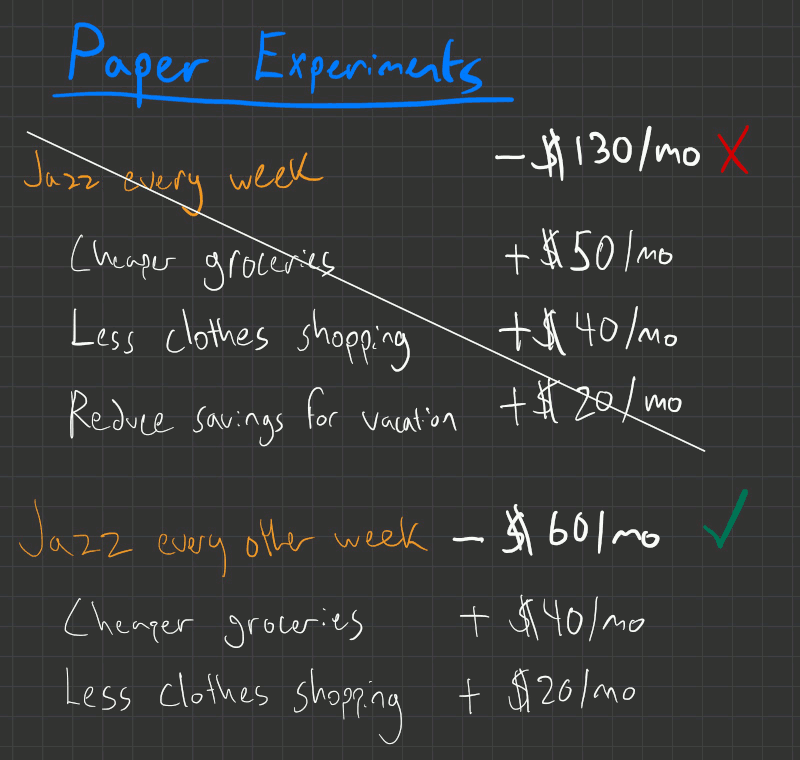

Phase 1: Paper experiments

No, you don't need a printer

These are thought experiments, run on paper (...or in software....or your head), where you imagine how it feels to change your spending in some way that, at least theoretically, would improve your life.

The most important part of paper budget experimentation is to avoid filtering yourself. Consider every idea that comes to mind!

Paper experiment questions usually are sparked naturally as you look at your budget allocations. They might be questions like:

- How can I afford to see live jazz every week?

- Would it be possible if I spent less on groceries?

- How long will it take me to save for a mortgage down-payment?

- What if I move to a cheaper apartment until I buy the home?

- Does it change these plans if I buy a motorcycle?

Designing paper experiments

With your budget written out, you should be able to effortlessly evaluate these types of scenarios. Start by adding the increased (or reduced) cost to your budget representing the desired change, and then tweak the other categories as necessary to make it work.

After each change, imagine how the real-life consequences of the change would make you feel.

If you're generating sufficiently unfiltered ideas, you'll need to get creative to balance your budget. You'll end up tinkering with categories you didn't expect -- spending or cutting in ways that makes you feel uncertain.

That's expected!

In everyday life, your mind makes similar automatic judgments about what spending is or isn't possible. They're fast, but they're not always right. Remember that you're experimenting and override these automatic judgements, thinking more closely that normal through all the positive and negative consequences of the budget changes.

Allowing yourself the opportunity to play scenarios out with real numbers is what will break you out of the "local maximum" of mental budgeting.

Phase 2: From paper to reality

With a real-life experiment, you take your paper experiment and change your spending behavior in real-life to understand if it is sustainable.

Usually, living out a set of spending decisions for a month or two will generate strong feelings (either positive or negative) about whether to make those changes permanent. These feelings can significantly increase your confidence in a budgeting change compared to running a paper experiment.

But real-life experiments always take more time, money, and energy than paper daydreaming about your budget. Constant real-life experiments will burn you out on budgeting.

So the trick is to continuously nurture paper experiments until you are confident enought to turn them into real-life experiments. I like to sit on my "sounds good" mental experiments for a month or so to make sure they'll be worth the effort.

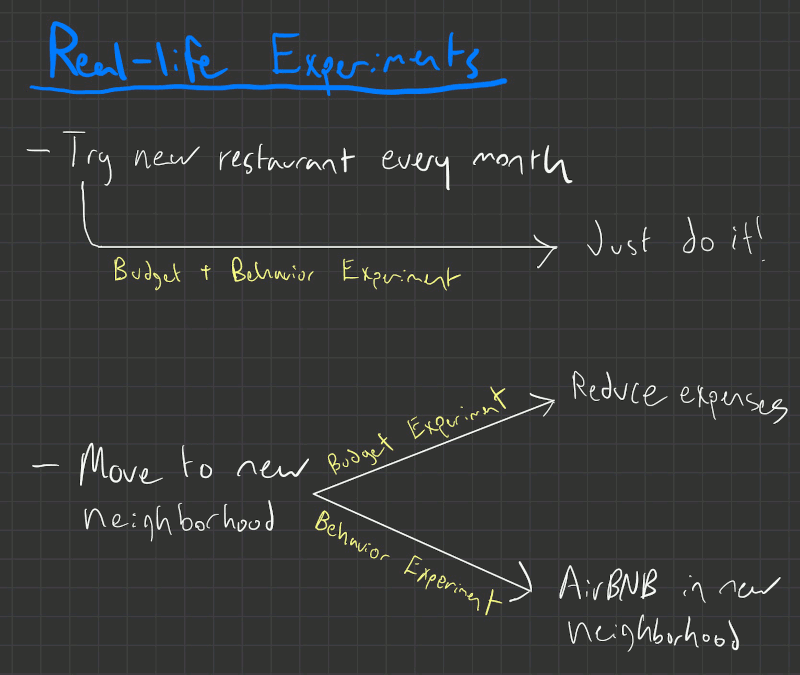

Running Real-life Experiments

Some real-life experiments are low-stake decisions that are easy to try. For those, go ahead and modify your budget and start living your new life! Usually, a trial period of 1-3 months is sufficient to decide whether to make the change, after which you'll want to evaluate:

- Did it work out as expected?

- Is it aligned with my personal values or life goals?

- Does it prioritize short-term or long-term needs, or vice-versa?

- Did I receive more fulfillment than what I gave up?

Low-stakes experiment example:

Looking at your budget makes you realize how meaningful date nights with your partner are. You want to try increasing the number of date nights by cutting a daily coffee habit.

This experiment is easy and risk-free to run for a couple of months -- what could you possibly lose? But other decisions, and often the most impactful ones, aren't nearly as easy to set up as experiments. Unfortunately, it's often the most significant decisions that get the most benefit from budget experiments.

High-stakes experiment example:

You're envious of friends who live in a trendier neighborhood. You want to try living in that neighborhood by reducing several other expenses.

In cases like this, it's helpful to separate the cash-flow change and the behavior change into two separate experiments. Run and evaluate each experiment separately and weigh the answers together afterwards.

Let's take another high-stakes example of deciding to quit a 9-5 and start your own business -- it's unlikely you can run this as a single temporary experiment. However, it might work as two independent experiments like this:

First, figure out what disposable budget items you'd cut to give your new business some runway. Try living on that budget for a couple of months as you're working at your full-time job. Is it even possible? Are there changes you could make to make it more livable? Are there revenue goals that you'd want to set for your business based on your experience of living under a different budget?

Separately, run an experiment to see how the day-to-day experience of starting your own business would feel. Maybe supplement a holiday with some vacation time or take unpaid leave so you can spend a few weeks heads down on it. Was it as amazing as you'd expected? Enough to make the other changes to your budget feel worth it?

Although running two separate experiments isn't a perfect test, it allows you to learn something about a new lifestyle with significantly less risk.

How to mine your budget for experiments

Although many experiment ideas may have easily come to mind, the most important insights often come from categories that you instinctively overlook. To uncover those, I recommend "mining" your budget.

To do that, scan through your categories and expenses, asking yourself applying any of the techniques below to them could improve your life. Or at least be worth an experiment!

Add spontaneity

If you don't see much spontaneity or variety in your spending, it could signal there's room to improve your budget.

Spontaneity is the spice of life. No matter how well you've planned, life will become increasingly bland without some variety. Signs of lack of spontaneity in a budget include overly specific categories, overly repetitive expenses, or an allocation overly focused on future instead of present spending.

Consider creating explicit budget categories that plan for everyday fun and check them once a month or so to remind yourself to keep your spending spontaneous.

Flush out "fake obligations"

It's healthy to avoid constantly second-guessing your recurring expenses. There's little to gain from shaking your fist at the rent bill every month when you love your neighborhood and you know you'll never consider leaving it.

But on the other hand, it's equally healthy to intermittently question whether what you consider to be obligations are truly obligatory.

To flush out "fake" obligations, consider your most significant expenses first (often housing, transportation, and food) and then continue down to the medium ones. If you were forced to cut any one of those expenses, how would you do it? And then, more importantly, how would you feel about it? For example:

- How would downsizing to an apartment that's $500/month cheaper feel?

- How would biking to work and getting rid of your car or train commute feel?

Most of the time, these won't seem like good options. After all, you chose these obligations for a reason. But tastes and needs do shift and you should be ready to adjust when they do.

Make a dent in long-term goals

Most tech workers I know have a strong motivation to "level up" at work. Depending on the person, that might mean building particular technical or people skills, succeeding on their team, or getting promoted.

But this makes it easy to neglect your personal goals and ambitions. What is the "next level" for your personal life?

Ensure that your budget reflects your personal long-term goals so you'll feel fulfilled even when your focus shifts away from work.

It can sometimes feel awkward to set and save for long-term goals that you don't feel confident in (e.g., if you want to save to start a family but don't even have a serious partner), but that shouldn't stop you from using your budget to think through the possibilities. Remember, you can always reallocate your savings towards long-term goals later!

Level up the volume on a passion

You can't travel to a different country every single year. You can't try a new restaurant every single week. You can't work only 20 hours a week. Insert your own denial of an unrealistic fantasy here.

Well...maybe you can? Sometimes we unwittingly limit ourselves from doing things we love out of habit. Almost anything is possible if you're willing to ruthlessly prioritize.

So why not set up some experiments to see if there's a way to level up one of your passions?

Nix "empty-calorie" expenses

Similar to our "fake obligations," we can have "fake pleasures." These are activities that at one time gave us pleasure but have had their effect wear off over time as they became more routine.

Some examples of this could be buying fast food for lunch at work (literally empty calories), always buying the newest iPhone, subscribing to too many video-streaming services, or leasing a new car every few years.

The point is not that any of these expenses, in particular, are frivolous and not worth the cost. Heck, I'm the person that paid $20 for a small chunk of cheese.

The point is that you should be mindful of which purchases are not bringing you the pleasure they once did and stop spending on those. Then put the money towards expenses that really make you giddy (even if they might be considered frivolous to others).

Tweak your balance of work and personal expenses

Since many tech workers consider their work as a core part of their identity, it can be tricky for them to recognize which expenses are truly personal. Clarifying the distinction between personal and work expenses, then running experiments that tweak the balance can be illuminating.

Some examples of work expenses that can masquerade as personal expenses:

- Commuting costs

- The increased cost of housing to be closer to work

- Phones or computer bought primarily to use for work

- Clothes bought primarily to wear to work

- Meals bought because there's no time to cook after work

- Travel or other leisure activities pursued primarily to take your mind off of work

Which trade-offs is your work stealthily forcing on you? After identifying them, run some experiments that tweak the balance.

These experiments are particularly useful for making significant life decisions like moving, switching employers, deciding to start your own business, or retiring early.

Go ahead and do it

As General Eisenhower put it, "Budgets are useless, but budgeting is indispensable."3 The key to budgeting is not developing the perfect plan but maintaining a lightweight process that continuously improves how you allocate your money.

So give yourself the leeway to shake things up, and go surprise yourself with some budget experiments!

The next article in the series will explain how to think through some trade-offs as you analyze your experiments -- time vs. money and present vs. future spending.

Key takeaways:

-

Budget experiments can improve your life by iteratively bringing your spending in tighter alignment with your life's pleasures and goals

-

It's most effective to run as many experiments as possible on paper before you spend the money, time, and effort to try them in real life

-

You can mine your budget categories for experiment ideas, such as adding spontaneity, focusing on long-term goals, and identifying fake obligations

Looking for the next article?

Follow me on Twitter or sign up for the email newsletter as soon as it's published.

There's more that's left to learn, including the practical steps to setting up your 401k and investment accounts. I'm in the process of writing those articles, and can't wait for everyone to read them. Your sign up would really encourage me to get a move on it.