Investing during a recession (Part 3/3)

Investing is as much a pyschological exercise as a financial one. A little preparation can help you stick to your plan when panic hits.

After reading the previous two posts, I hope you're convinced that buying and selling stocks during a recession isn't as smart or as easy as it seemed at first blush. But rational argument alone cannot prevent the strong emotional reactions that come in a time of panic.

Since severe recession often comes with severe world problems, we're forced to make financial decisions when we're most emotionally vulnerable. Humans have evolved to react instinctively to feelings of danger, not to stoically calculate a rational response.

For this reason, it's useful to think deeply about how financial recession works before you're thrust into an emotional state — How did past recessions affect investors? How much control do investors actually have once a panic begins? Why do investors choose to invest despite the risk of recession to begin with?

This post should help you crystalize your thoughts on recession so that you'll be emotionally prepared when it comes. If you haven't read the first two posts already, I recommend you start with them:

The Three Posts

Follow me on Twitter or sign up for the email newsletter to be notified about future posts.

Prepare to do nothing

Marcus Aurelius, the last great Roman Emperor, was a student of history and human psychology, and an expert at responding to anything life threw at him in a calm and rational manner. He was not born with this ability, it was the result of intense mental preparation. In his personal meditations, he constantly reminded himself:1

The world is nothing but change...Nothing is stable, not even what’s right here.

He never expected Rome to be struck by rebellion and plague at once, but he understood that it was unlikely for an emperor's world to remain stable indefinitely. After years of training in history and philosophy, no disaster would catch him off guard. He responded to the rebellion calmly, even promising to show mercy to his usurpers, and was ultimately able to save the Roman Empire from ruin.

Good investors expect losses

Although few investors will face the same level of challenge that Marcus did, we can apply the same type of mental preparation to our financial planning.

Financial history is really just a series of unexpected events. In the last 20 years, the stock market has experienced unprecedented growth, but also three major crashes. And we shouldn't be surprised — booms and busts are the norm, not an exception. Temporary periods of economic loss, even periods lasting years, are a part of investing.

In fact, the only reason stock investing is profitable is because there is a risk of loss. If there were no risk at all, the price of stocks would be bid up so high that they would be no more profitable than a savings account. The risk of a drop in stock prices is not a reason to avoid the stock market. The potential for profit created by risk is the reason anyone invests in the stock market in the first place.

When financial panic hits, remember: it was bound to come eventually. You don't like it, but you have prepared for it. It will only make things worse to change your investments out of fear.

Crossing spilled milk off the grocery list

By the time you get news of a financial panic, it is too late to react. Stock prices have already dropped. As the bad news that caused the panic went public, money managers around the world immediately made their trades. Selling stock after prices have already dropped is useless, like crossing milk off a grocery list after you've already spilled it.

But you can calm your nerves by realizing that the stock market will not continue to drop if the panic plays out as expected. Once a panic has driven stock prices down, the actual event itself won't have any effect on stock prices, unless it turns out even worse than predicted. For example, if there is news of a pandemic breaking out, stock prices will drop to reflect the financial damage expected by the pandemic. When the damage eventually occurs, prices won't drop. They will only drop to the extent the damage was worse than originally expected.

In this situation, many investors predict that the damage will be worse than everyone expects and use this as a reason to sell stocks. But a mentally prepared investor realizes that, unless they have some special knowledge of the situation, they shouldn't let their fear convince them that they can predict the future better than others.

Wharton finance professor and stock market historian Jeremy J. Siegel puts it like this:2

Markets do not directly respond to [what happens in the world]; rather, they respond to the difference between what the traders expect to happen and what actually happens.

When stock prices drop, the milk has already been spilled. Since you knew it would happen eventually, the appropriate reaction is to carry on with your plans, not to cross it off the grocery list.

Modern Pandemics: Putting the theory to the test

Enough philosophizing. Let's put this theory to the test! As I write this (in August, 2020), we're living through the worst pandemic since 1918. The US economy is in recession and there's wide fear about how the stock market will react. But is the fear justified based on history?

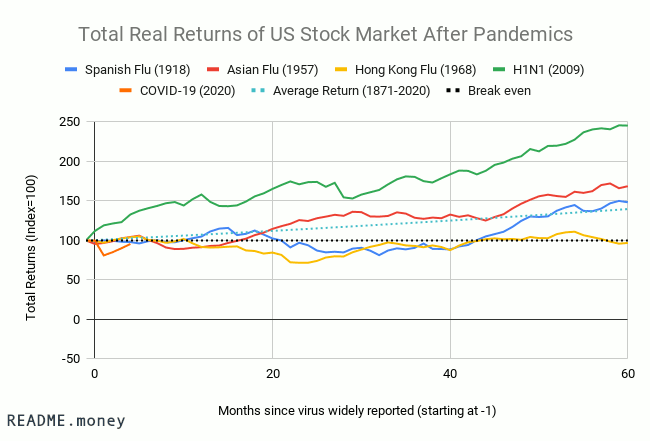

To find out, I plotted US Stock Market returns after each modern pandemic:3

The modern pandemics took a severe human toll on the US, killing between 12,000 (H1N1, 2009) and 675,000 (Spanish Flu, 1918) Americans. The primary public health impact of every modern pandemic was felt within a year or two of their initial spread.4

Despite the human loss, it is difficult to see any long-term impact that the pandemics had on US Stock Returns. The returns are distributed fairly evenly around the average yearly real return of the past 150 years (appoximately 6.8% per year).

3 out of 4 of the pandemic periods actually had higher than average returns. The best-case (H1N1, 2009) posted a +20% yearly return while the worst-case (Hong Kong Flu, 1968) posted only a -1% yearly return (CAGR). The market seemed to move unpredictably based on other things happening at the time (whether that was a World War, inflation, or economic recovery) rather than based on the pandemics themselves.

Keep this example in mind when the next financial panic comes. Even periods of high uncertainty, when thousands were dying, didn't necessarily cause a market downturn.

Risk-Averse investing during pandemics

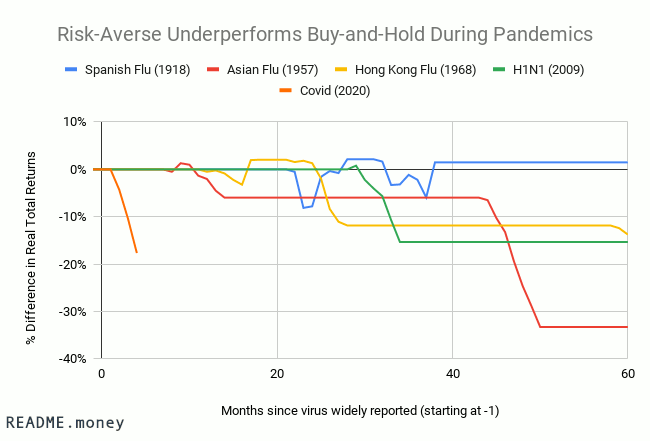

A risk-averse strategy like we discussed in Part 1 would have fared particularly poorly during pandemics. In this risk-averse strategy, the investor sells stocks after any 10% price drop from the peak, and buys back six months later.

The graph below shows the underperformance of this strategy during modern pandemics compared to simply holding on to the stocks from the beginning of the pandemic:5

The Risk-Averse strategy performed significantly worse in 3 out of 4 of the 5-year periods. In the worst case (Asian Flu, 1957), the Risk-Averse investor would have had a 33% lower balance than the Buy-and-Hold investor after 5 years. In the best case (Spanish Flu, 1918), they would have had a 1.5% higher balance after 5 years. As this article is written, during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020), the strategy seems to be performing particularly poorly: the Risk-Averse investor would have a 18% lower balance after just four months.

Interestingly, the underperformance of the risk-averse strategy seems driven by the unpredictable variance of each period rather than the overall direction of the stock market. For example, during the period of the Hong Kong Flu (1968), the US stock market had negative returns over 5 years, but the risk-averse strategy did not help avoid that risk. During the Spanish Flu (1918), the market had a small return over 5 years, yet the Risk-Averse strategy performed slightly better than Buy-and-Hold.

The data fits our theory of the futility of reacting to world events for personal investing. Many thousands of deaths seemed to have had very little effect on stock returns. And by panicking in a time of crisis, investors usually just dug themselves further into a hole.

So what should you do?

How you should change your investments during any period of economic uncertainty? In the words of John C. Bogle, the late founder of Vanguard:

Don’t do something. Just stand there!

There are surely things you can do to keep yourself and your loved ones safe during any particular crisis. But changing your investment strategy isn't one of them. From a financial perspective, you should follow the advice that virtually all financial advisors give irrespective of the state of the economy or recent events:

Keep several months of living expenses in cash for cases of emergency. Then invest in the stocks, bonds, and cash according to your plans and risk tolerance. Do not react to the news.

Key Takeaways:

-

Financial recessions and stock market crashes are a normal part of investing. Smart investors anticipate these events and stick to their plan

-

Stock prices move based on the market's expectations, not based on events themselves

-

Even grave world events like pandemics have unpredictable effects on stock market returns

Follow me on Twitter or sign up for the email newsletter to be notified about future posts.